Through one of the most competitive fellowship programs in the world, UNC Charlotte Africana Studies scholar Oscar de la Torre has been named the Anthony E. Kaye Fellow at the National Humanities Center in the coming academic year.

De la Torre will join 35 other leading scholars chosen as fellows from 638 applicants from universities and colleges in 16 U.S. states and from Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Nigeria, and Taiwan. Each fellow will work on an individual research project and will have the opportunity to share ideas in seminars, lectures, and conferences. The National Humanities Center is the world’s only independent institute dedicated exclusively to advanced study in all areas of the humanities.

“We are proud to support the work of these exceptional scholars,” said Robert D. Newman, center president and director. “They were selected from an extremely competitive group of applicants, and their work covers a wide gamut of fascinating topics that promises to shape thinking in their fields for years to come.”

With the fellowship, De la Torre will focus on his second book, a study of Afro-Cubans – free and enslaved, women and men – in the city of Matanzas, Cuba during the nineteenth century. His rich and stimulating book will include digital mapping and what he describes as shocking findings using archival evidence.

De la Torre is an associate professor in the Department of Africana Studies and also a faculty member in the Latin American Studies program. His research focuses broadly on slavery and the post-emancipation period in Brazil, Cuba, and the U.S., with a special focus on the connections between environment, labor, and identity.

He is also interested in the oral history of slavery; in present-day black peasant movements across the Americas; and in the comparative analysis of race relations in Latin America and the U.S.

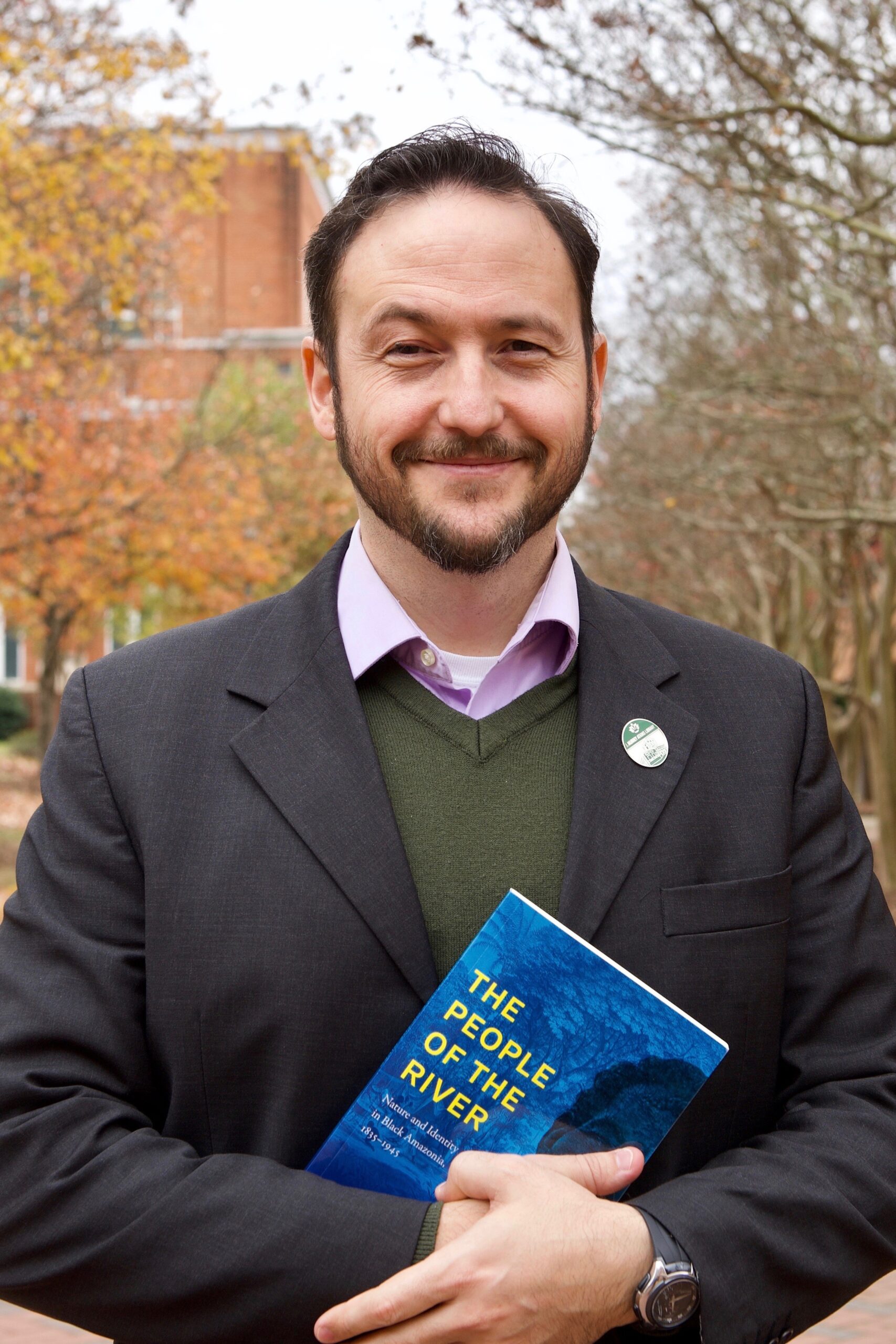

His first book, The People of the River (UNC Press, 2018), is a social and environmental history of black communities in Amazonia that has been described as making an important contribution to the history of the African diaspora. The book won the 2019 Outstanding First Book Award from the Association for the Study of the Worldwide African Diaspora, the 2020 Best Book on Amazonian Studies Prize from the Latin American Studies Association’s Amazonia Section, and an honorary mention from the Brazilian Studies Association for its 2019 Roberto Reis Book Prize.

He has co-edited special issues at Boletín Americanista on post-emancipation societies, and at Ofo: Journal of Transatlantic Studies on community engagement in the African Diaspora. He has served as a book and article reviewer for Hispanic American Historical Review, The Americas, The Journal of African American Studies, Latin American Research Review, and others. He earned a doctorate in history at the University of Pittsburgh and a post-doctoral fellowship at Yale University’s Gilder-Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition.

De la Torre’s Thoughts On The Fellowship

Q. How will the fellowship benefit and advance your research?

My book will be a collective biography that focuses both on individual life episodes – birth, work, leisure, disease, death – and on the collective trajectory of Black Matanceros, from slavery to nation-making. At the bottom of this exploration lies a concern with the peculiarities of race in Latin America. To what extent did inter-racial sociability and high rates of racial mixture translate into more or less racism? What were the achievements and the pitfalls of the political projects based on those realities?

This will be a complex book with digital mapping and a database behind it, and also with a number of shocking findings using archival evidence. The fellowship will allow me to invest the necessary time and energy to write it.

Q. What is the significance of your research and this book?

This is a very significant piece of research. First, because the slave and free Black populations of Cuban cities have received much less attention than their plantation counterparts, apart from a few classic and contemporary works, naturally.

Second, because the book will have an important gender component, for the practice of Afro-Cuban religions varied by neighborhood depending on the predominant gender and the slave vs. free status of its inhabitants. There are not a lot of studies on slavery and gender in Cuba, either.

Third, most readers don’t know that the first wave of Cuban labor unions in the 1880s was led by the members of an African (Efik and Igbo) secret society in Cuba known as Abakua. African roots are key to the history of organized labor in the Americas, and members of the public know little about this.

More broadly, studying race in Cuba is absolutely essential, because this is the most successful country in the Americas in combating racial inequality. In many ways their strategies cannot be replicated in countries with free-market-based economies, but still there are many lessons to learn. While the island is obviously not a racial paradise, it is definitely well ahead of us in providing equal opportunity to all its citizens across race.

Many of our students grow pessimistic when they see news about police aggressions against Black men and women – something understandable, naturally. However, while we need to understand and comfort them, in the long term our duty is to design and discuss solutions. As we can see in all countries in the world, racial inequality diminishes by employing certain public policies, and worsens when governments implement others. Our task as scholars is to understand how both sets of policies work, so that policymakers can then access that knowledge to make the right choices.

Q. Please describe how you bring your research into your classrooms and other work with students?

I do this in two ways. First, by incorporating cutting-edge scholarship to my class discussions and lectures. New census data is coming out every year about racial inequality in Latin America, making life somewhat “difficult,” but also fascinating, for those who study Afro-Latin America.

Second, I love to incorporate original documents into my classes, so that the students see how what people said and did a century or two ago is actually not so different from what people say and do nowadays. Once they relate to individuals who lived in the past their perspectives change, and the class becomes much more engaging. Students love it when we read about the lives of Black Conquistadors, for example, or about how enslaved women succeeded much more often than you would suspect in colonial Latin America when they brough court cases to request a change of slaveowner, or to settle a price for their freedom. Using original documents also allows you to train the students in making arguments based on evidence, the skill that lays at the basis of critical thinking.

Q. What does it mean to you to receive this specific fellowship?

This is a great honor! The NHC is probably the leading research center nationally for those who work in the humanities. In addition, spending that time surrounded by other humanities scholars who will be carrying out interesting and stimulating projects is priceless. I have done this sort of fellowship before, and the exchange of ideas ALWAYS ends up fertilizing your own work.

Words and Image: Lynn Roberson, College Communications Director, with Oscar de la Torre